The Church Without a Christmas Tree

I grew up in the Church of Christ, a tradition shaped as much by its doctrine as by its careful adherence to what we understood as the inspired Word of Truth—New Testament scripture. Christmas—Christ Mass, after all—carried with it echoes of liturgy, ritual, and ecclesial authority that did more than make us uneasy; they were not supported by scripture. It felt too “Catholic.” Nativity scenes, Christmas trees in the sanctuary, pageants, and concerts all felt suspect, as if they edged too close to something we had worked hard to distinguish ourselves from.

Our doctrine emphasized Jesus’s death, resurrection, and promised second coming—the salvation story in its fullest and, to us, most biblically faithful form. That was where the weight belonged. Christmas, when it appeared at all in worship service, seemed secondary. There might be a sermon in December, but it was usually framed as a reminder not to let sentiment distract us from the real celebration: the cross, the empty tomb, and the anticipation of Christ’s return.

Beginning sometime in the 1980s, our monthly church fellowship included a “greedy Santa” party in the fellowship hall—an accommodation that felt almost humorous in its contradiction. At home, though, the birth of Christ was acknowledged and celebrated in quieter, more personal ways. Christmas existed, but it lived more in our houses than in our sanctuaries.

Wonder, Anyway

Even so, Christmas always carried a sense of wonder.

In my family, it was joyful and wonder-full. We celebrated the birth of Christ. We sang the songs, set out nativity scenes, and watched cartoons that made room for the baby Jesus alongside Rudolph and Frosty. I developed a passion for Little Debbie Christmas Tree Cakes that continues to this day. But Christmas was never treated as a central moment of worship. It was present and honored, but it did not occupy the same place in our worship as the cross and the resurrection.

Instead, Christmas lived easily among us. It shared space with Santa Claus and stockings, with family meals and laughter, with the ordinary magic of being together. Faith was there, woven into the fabric of the season rather than standing apart from it or asking to be the center of attention.

We sang Away in a Manger and Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas with equal sincerity.

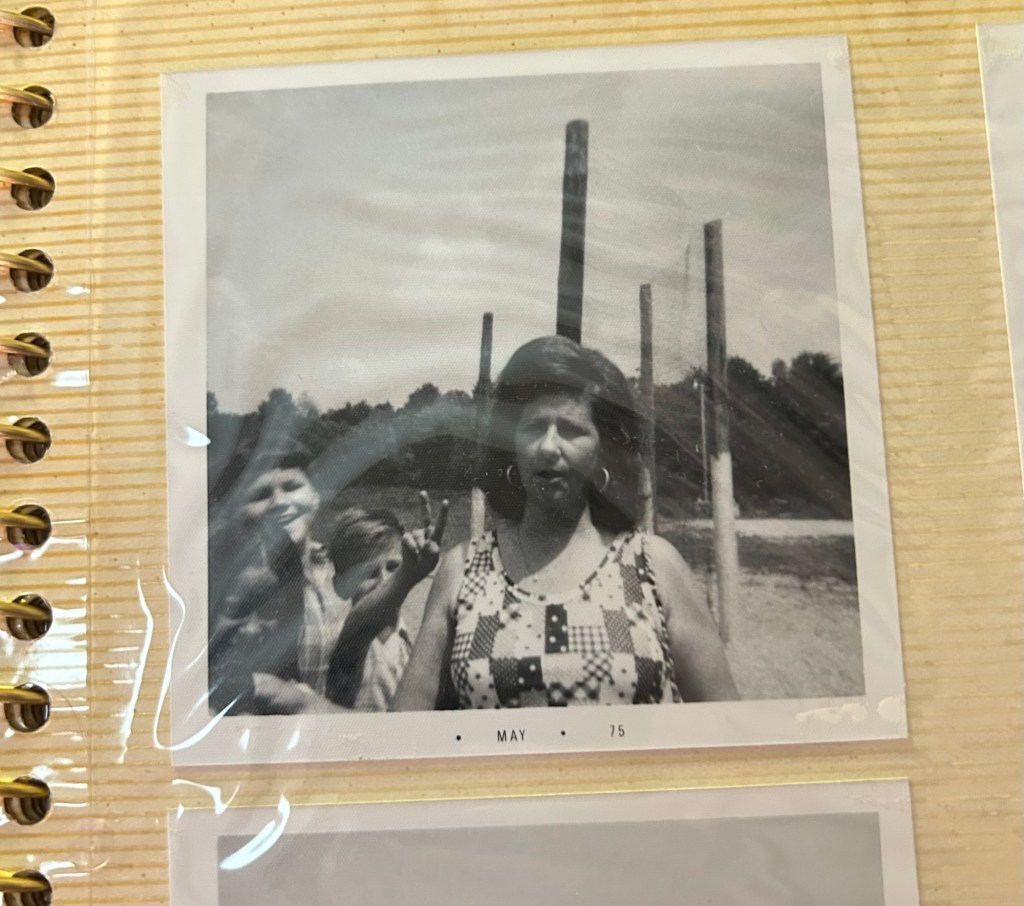

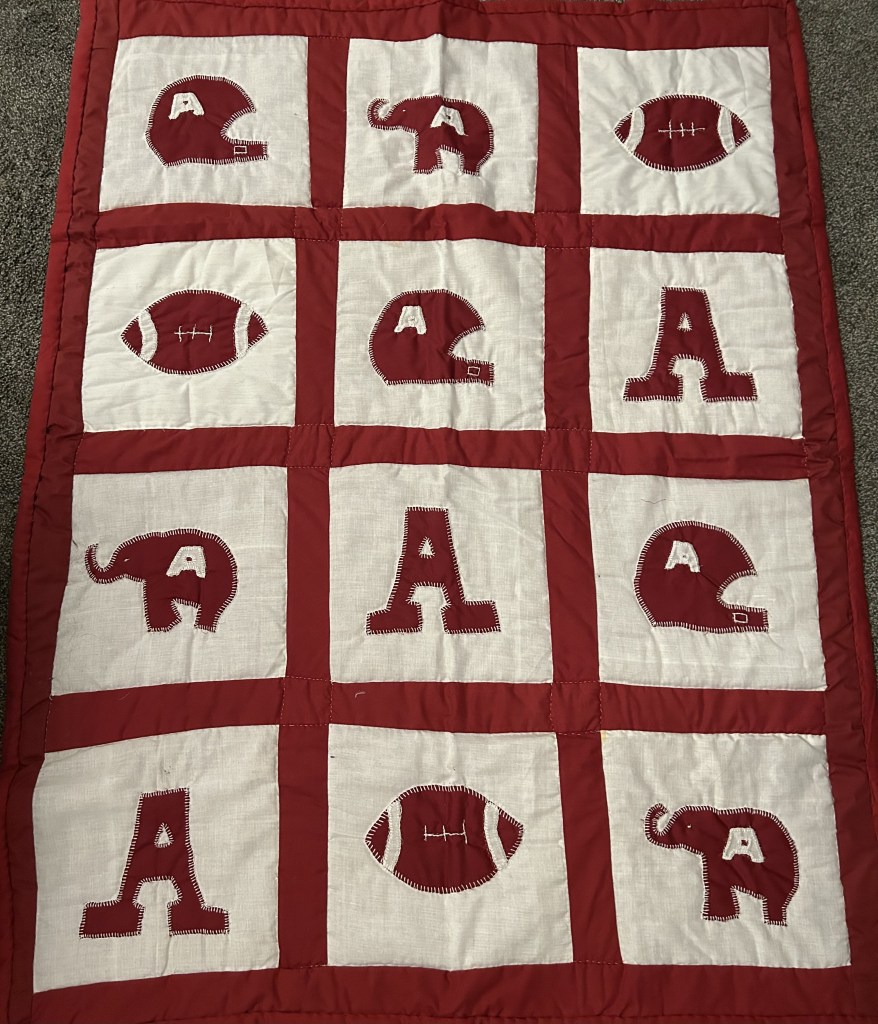

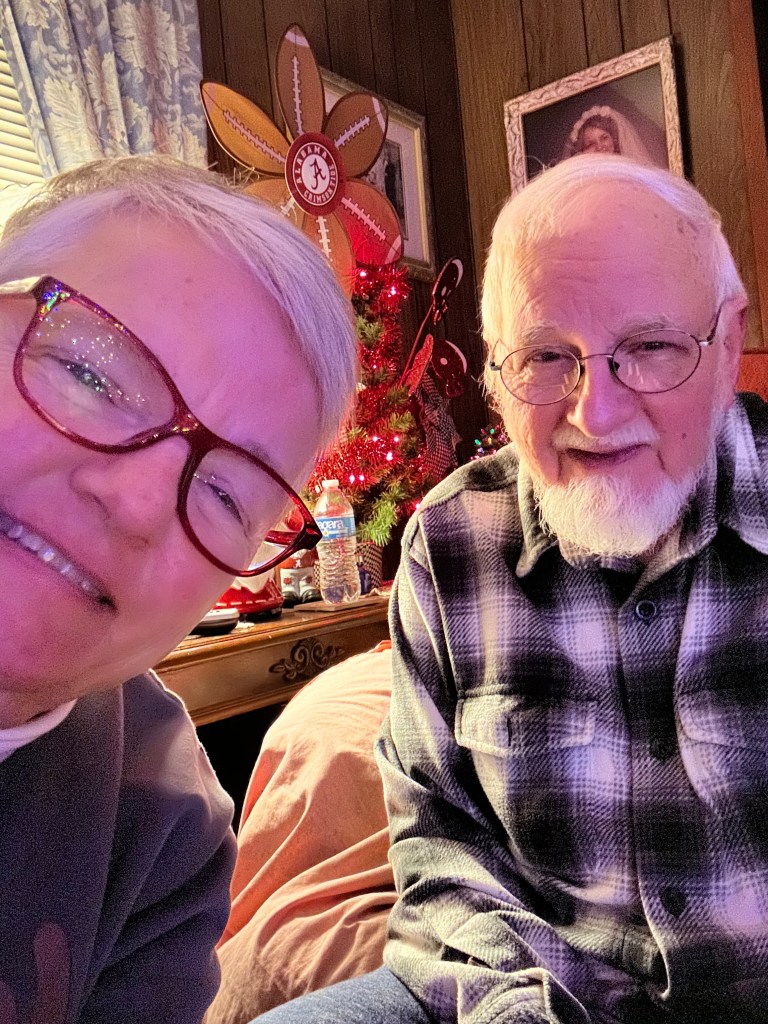

Some of my strongest Christmas memories are of going to town with my mother—just the two of us—walking down Main Street in Russellville, Alabama. We stopped at Elmore’s and White’s, always went to the bank, and did a bit of Christmas shopping. We also made our rounds to TG&Y and Bargain Town U.S.A. Going to town with Mother is one of the memories that has never faded. She loves Christmas. I suspect that is where I get it.

Perhaps the magic was not Christmas itself, but Mother making it all come together. Daddy—God bless him—was assembling bicycles late into the night, helping Santa Claus eat the cookies and drink the milk when no one was awake, and getting up early to turn on the heater before us kids stirred.

So Christmas has always carried for me the emotions and images of Advent: love, peace, and joy. Yet as I’ve grown older—and as I’ve celebrated Advent more intentionally in churches I joined later—I’ve come to realize something important was missing from my early experience, at least as I have come to understand it now.

Hope.

That missing note, I’ve learned, is at the very heart of Advent: not the anticipation of Christ’s return, but the radical, trembling hope of waiting for Him to come the first time.

Before I go any further, I want to be careful about how this contrast is read. I don’t mean to disparage the Church of Christ or its seriousness about salvation and the life to come. The emphasis on the afterlife was never meant to diminish this one; it was meant to anchor it. There is something steady, even bracing, about a faith formed around the cross and the resurrection, around the somber knowledge of what comes on Friday during Holy Week and the refusal to look away. That certainty shapes the tone. It is sober, resolved, and grounded in knowing how the story ends.

Advent, I am learning, asks for something different. It invites a looking forward that is almost visceral, a waiting marked by anticipation rather than knowledge. During Advent, we do not yet know what is coming, even though we think we do. Christmas and Easter are both joyous occasions, yes, but they are not the same kind of joy. Easter joy comes after suffering we already understand. Advent joy comes before anything has happened at all. It is hope without proof, expectation without resolution.

Perhaps that is why Advent feels so unfamiliar to me. I was formed in a tradition that lingered near the end of the story. Advent asks me to return to the beginning, to wait not with certainty, but with hope.

That difference between certainty and waiting is something I didn’t fully understand until I found myself, almost by accident, living Advent rather than merely knowing about it.

Learning Advent by Living It

Just recently, we joined a church that could not be more different from the one I grew up in.

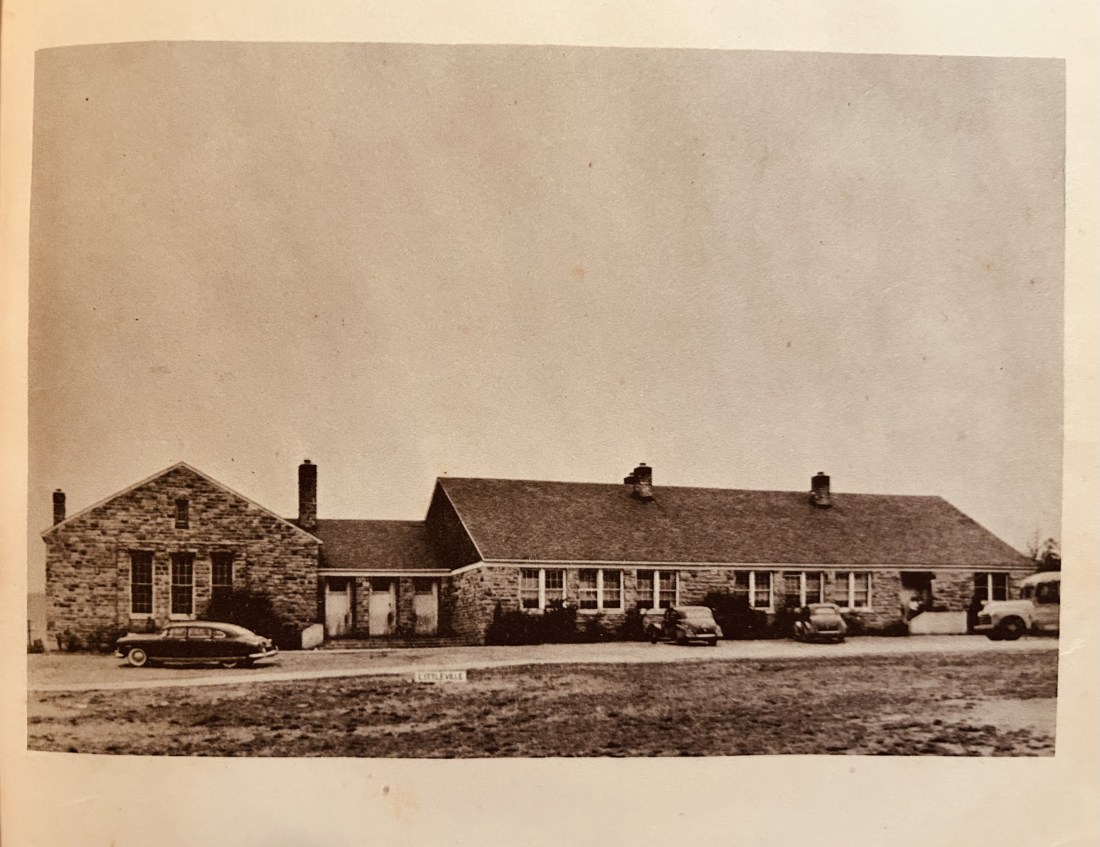

Trinity United Methodist Church sits at the end of our driveway—practically in our neighborhood—and has been there for over a hundred years. We watched carefully last year as the United Methodist Church faced its painful and very public division. We waited to see whether Trinity would stay or go. They stayed. So we went.

Well—I went first.

Returning to church was part of my larger journey back to music. I wanted to sing again. I wanted a choir. So I showed up, and they welcomed me. Then Sarah came. I can say, without exaggeration, that I have never felt so genuinely welcomed in any congregation.

Of course, in a liturgical church, if you arrive in the fall, you don’t ease into Christmas—you begin preparing for Advent.

Trinity has all of it: the church calendar, the seasons, the art, the rhythm of the year itself. And it has a gifted music director, Ben Chumley. Music is not ornamental there; it is formative. Part of Trinity’s long tradition includes a concert series—bell ringers, piano recitals—and on the Sunday before Christmas, a full choir cantata, offered as a concert for the community.

I had never sung in an hour-long Christmas cantata before. It is exhausting—poignant and fulfilling, but exhausting.

At the same time, the sermon series centered on the coming of the Christ Child, and Sunday school was immersed in a deep study of Advent, framed by John Wesley’s theology. I knew what Advent was, of course, at least in name. I associated it with calendars and chocolate, with Advent functioning more as a reference point for Christmas than as a practice, something observed from the outside rather than lived. What I had not understood was Advent as a way of inhabiting time itself, a season that asks something of you slowly, deliberately, and in community.

Then one Sunday after service, Ben approached us and said, “I’m planning the lighting of the Advent candles this year, and I want to represent all kinds of families. I wondered if you and Sarah would like to light the first candle.”

So there we were—new members, still learning our way around the sanctuary—and suddenly we were the first family of Advent.

Our candle was peace.

You had better believe Trinity has a children’s Christmas pageant. There were painted backdrops of Bethlehem, shepherds with headgear slightly askew, stars projected onto the ceiling. Children of all ages belted out The First Noel at the top of their lungs. Candles glowed in the windows. The chancel was full.

From the choir loft, I expected—modern church attendance being what it is—that maybe two-thirds of the usual congregation would show up.

Instead, the church was full. This wasn’t novelty. This was a neighborhood showing up for something it clearly understood as theirs.

What struck me most, though, was how hope was being practiced, not merely preached. Alongside the music and liturgy, the church’s auditorium filled with donations for local children—gifts, necessities, abundance. Hope, in this space, was not about someday escaping the world. It was about showing up for it.

That was new for me.

Hope, in my religious formation, was almost always about heaven—and, implicitly, about avoiding hell. I didn’t have language yet for hope as active, communal, and embodied. Wesleyan theology was quietly teaching me something different: hope as something you do.

I should add that this wasn’t ignorance on my part. I had studied the church calendar before and even took a full course on it in seminary at McAfee. Sarah, who grew up in England, seems to have absorbed it almost by osmosis sometime in childhood. But knowing about liturgy and living inside it are not the same thing. What was happening at Trinity was not instruction; it was formation.

I haven’t left fundamentalism. I don’t think that’s possible, any more than it could ever leave me. It formed me. What I am learning now is not replacement, but expansion. This way of waiting, this attention to beginnings rather than endings, is becoming part of my formation too.

On the night of our final choir rehearsal before the cantata, I walked home through the neighborhood in silence. The street was lit only by Christmas lights and the moon, their glow softened by fog hanging in the air. We don’t get much snow here, but the light did the same work. Everything was hushed. All was calm. All was quiet.

I felt joy. Not only for the coming of the Christ Child, but for the possibility that the world could feel like this more often. That peace might be practiced, not just promised. And that, somehow, I could be part of it.