What I Learned From My Teachers

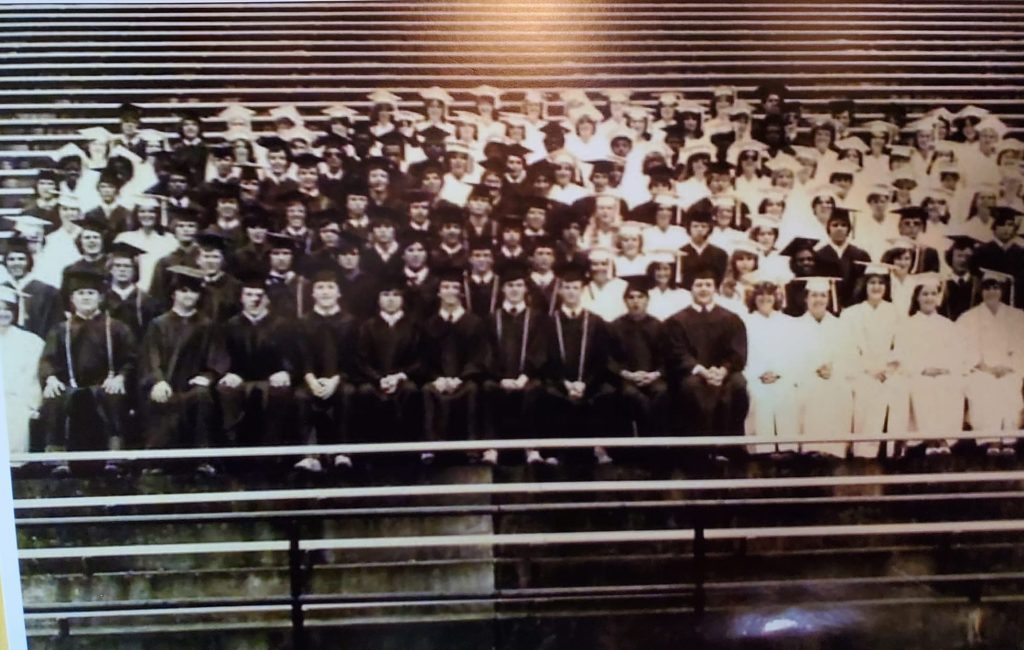

From Part 1: There’s a lot we carry from our school days—the lessons that stick, the ones that shape us in ways we only realize years later. I’ve been thinking about the teachers who left a deep impression on me, and how those early experiences continue to resonate as a quiet, steady presence in my life and work today. This piece (Parts 1 & 2) is dedicated to the teachers who shaped me, and I want to honor them by name.

Part 2: Miss Thorne, 7th Grade Math: A Lesson in Apology

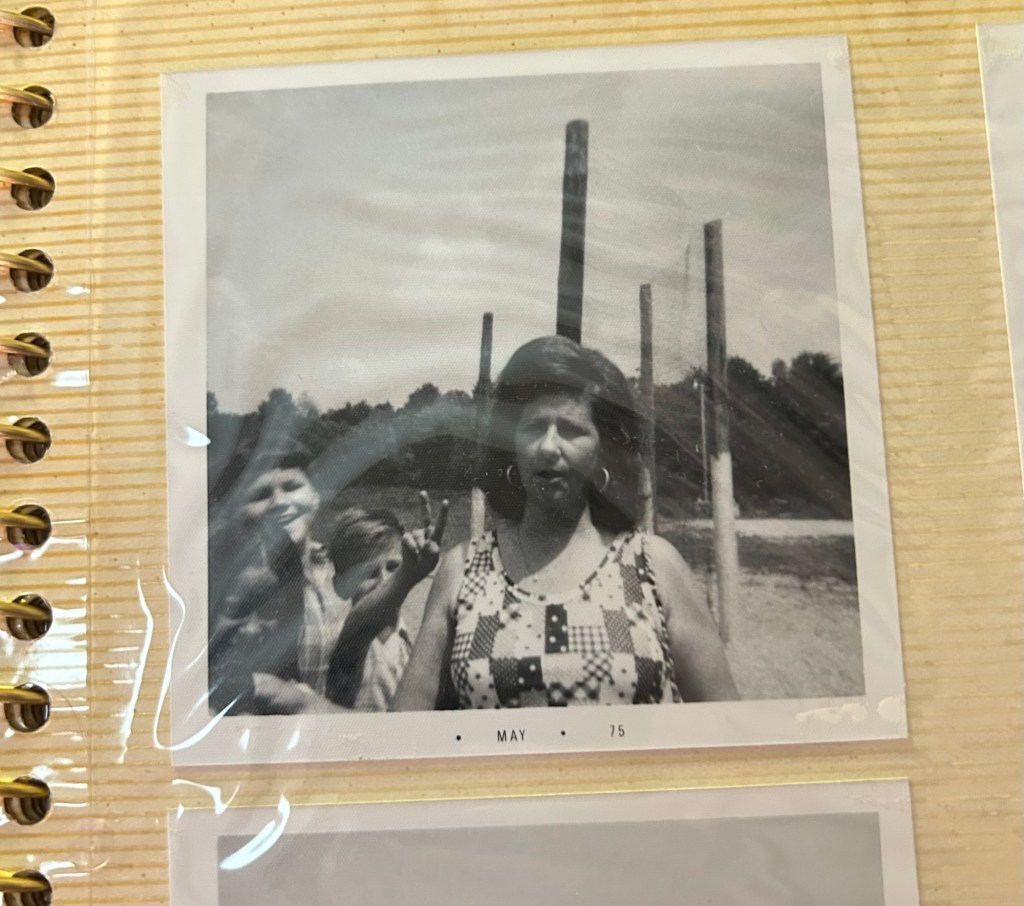

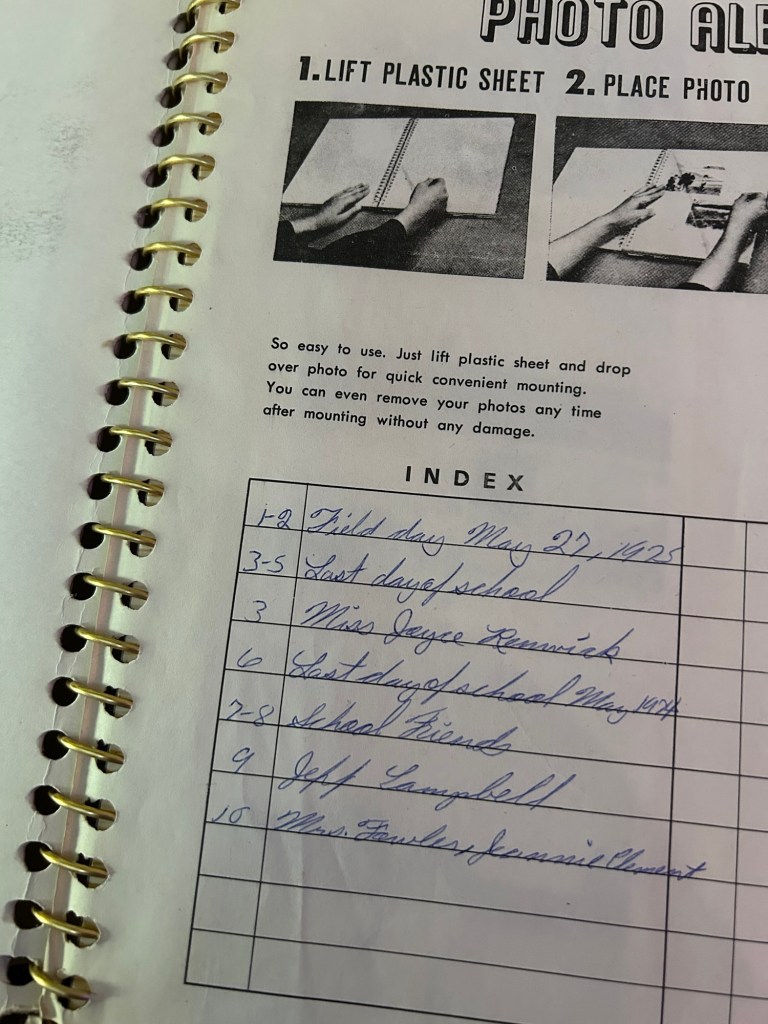

Miss Janice Thorne, who became Mrs. Berry during our 7th-grade year, is the only teacher I ever apologized to as an adult. My behavior in her class was atrocious. I vividly remember entertaining my classmates by hiding in the classroom while she searched the campus for me—the day the principal, Mr. Morgan, called my dad. Not my mom. Dad. I don’t remember acting out much after that. Like Mrs. Wells, Miss Thorne had the unfortunate task of competing with Miss Renwick for my attention, but unlike Mrs. Wells, she wasn’t a natural commander. I’m really sorry, Miss Thorne.

Miss Thorne also had the misfortune of being assigned to teach us P.E., which required her to wear gym shorts, crew socks, and SeaVees gym shoes. For some reason, this embarrassed me, though I couldn’t have explained why. She was also a member of a neighboring congregation, so I saw her off and on through the years. That made my apology all the more meaningful when I finally had the courage to offer it.

Probably unsurprisingly, Janice left teaching the year after I had her as a teacher. I have reflected on whether my behavior might have contributed to her decision, and my small consolation is that she likely made a good deal of money by going to work for TVA. Miss Thorne—Mrs. Berry—died in 2023, and I am so glad I had the chance to show her respect as an adult.

Mr. Morgan, Principal and 7th Grade Social Studies: The Importance of Being Remembered

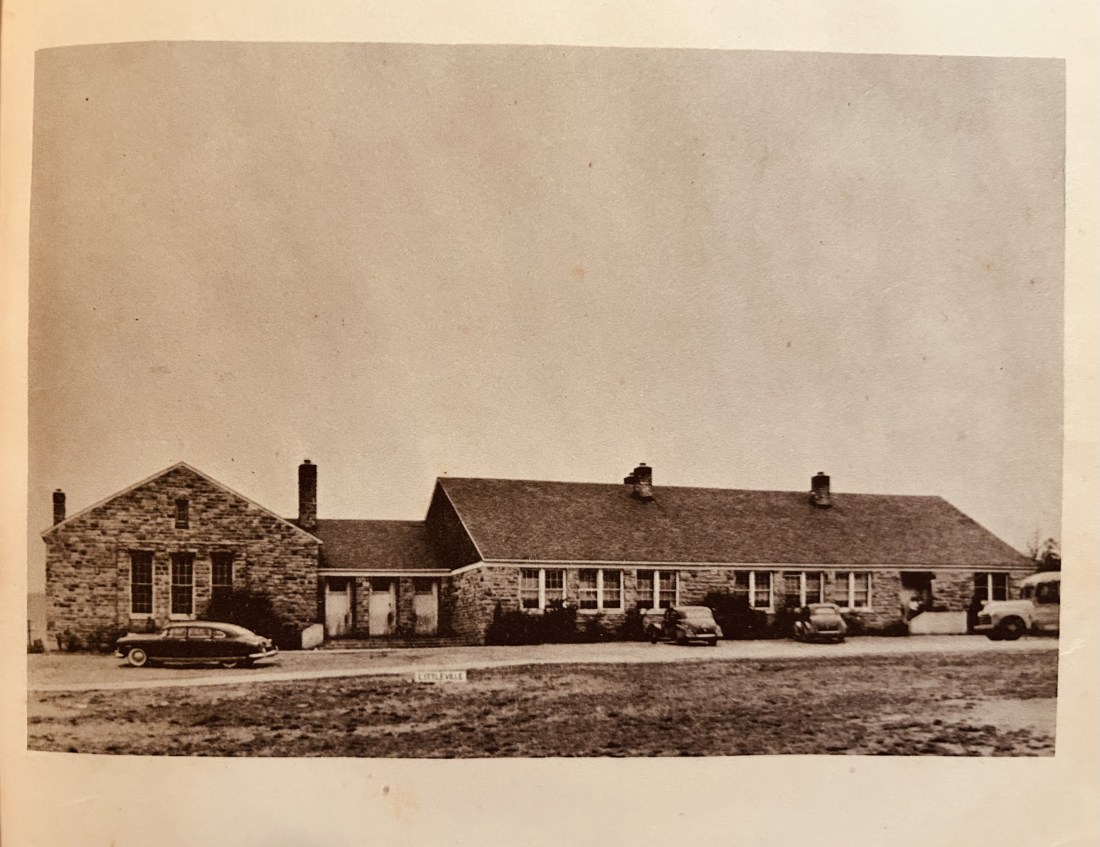

Mr. Morgan was the principal of Littleville School and also taught us 7th grade social studies. He was tall, having played basketball in his younger years, and he coached our teams with the same towering presence. His other claim to fame was that he had fought in the Korean War alongside Dan Blocker, who played Hoss in the very popular Bonanza TV show. I was glad to learn that Mr. Blocker was a nice person. Mr. Morgan regaled us with stories like these during social studies—and come to think of it, the Korean War was part of the curriculum. Mr. Morgan had the longest face I’d ever seen–one can’t help but recall Lurch from The Addams Family–and he spoke with a distinct impediment. We students discussed it and surmised that his tongue was attached to the bottom of his mouth—at least, that’s what it sounded like when he talked. But we quickly learned to understand him, and his speech became just another part of who he was.

Every year I attended Littleville, I earned a paddling from Mr. Morgan. Unlike Mrs. Fowler’s little red-painted ping pong paddle that intimidated second graders, Mr. Morgan’s paddle was a serious piece of wood—it must have been two feet long and was covered in signatures from its many recipients over the years.

In the early 1990s, Littleville School was closed due to low enrollment. The town had suffered during the recessions of the 1970s, and eventually, the numbers just weren’t there to keep the school open. Before the doors closed for the last time, a “homecoming” was held for everyone who had ever attended. That included my parents, my brother, neighbors—even my grandparents. I was a grown young woman by then. My parents were reminiscing with Mr. Morgan, who chose to retire rather than move to another school. He looked at me and said, “I remember when I gave you a paddling one time, Ugena. I had to hold back a laugh when you looked up at me and said, ‘Mr. Morgan, this is going to hurt me more than it hurts you.'”

A 20-year career, and he remembered a joke from a 10-year-old girl. Because I was funny and smart. I had been memorable. That, I think, is my main lesson—that these people thought enough of me to remember me.

Mrs. Mansell, 9th Grade Algebra: Making Math Make Sense

In 8th grade, I transferred from Littleville to Russellville to join the RHS Marching 100 Band. My parents really sacrificed to make this happen, commuting me to school a half-hour away instead of the five-minute trip to Littleville. Almost every teacher I’ve mentioned so far had told my parents that I needed enrichment to keep me busy—that my acting out was because I was smart. That made an impact, so I went to Russellville instead of following my Littleville classmates to the county school. I have often wondered how different my life would have been if I had taken the natural path instead of forging the one I did. Two roads diverged…

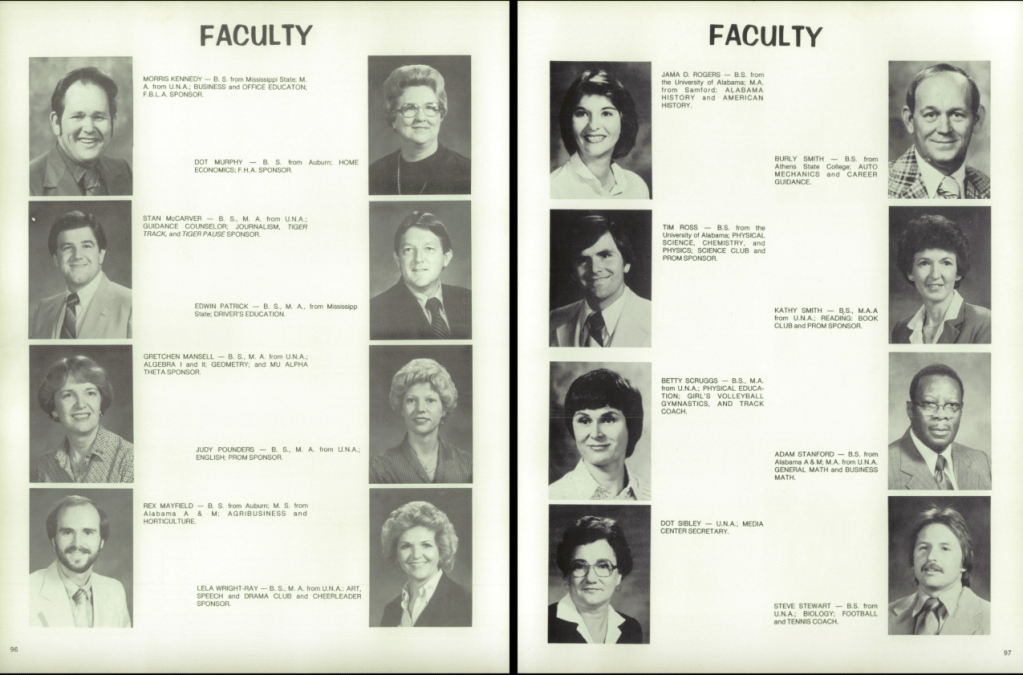

At Russellville, Mrs. Mansell stood out. She had real presence. She taught 9th grade Algebra and made math understandable in a way it hadn’t been since Mrs. Wells. Her father, E.L. “Prof” Williams, had been principal at Russellville High from 1937 to 1957, and my dad even remembered “Mickey” Mansell helping him register as a new student his ninth grade year. She connected with us, made herself available, and showed patience beyond measure. I remember being at a slumber party before exams, and a group of us girls called her for help. She patiently tutored us over the phone, and we all did well on exam day.

Despite her dedication and deep roots in the school’s history, Mrs. Mansell wasn’t allowed to teach upper-level math in the late 1970s. Those classes were reserved for a male teacher who prided himself on making his classes competitive. He openly stated that he taught to the valedictorian and salutatorian—to weed the rest of us out. I was weeded out of trigonometry in the first week. Discouraged and disheartened, I switched to Home Ec. I decided I’d rather study European and American furniture styles than endure that feeling on a regular basis.

I suppose I learned a lesson from him too—but of all my teachers, his was the biggest lesson on what not to do.

This piece is dedicated to the teachers who shaped me, and I want to honor them by name. They were the steady presence that guided a little girl from the country, who against all odds, would leave Littleville and go on to earn a doctorate and become a professor. I grew up knowing I was the “smart girl,” in part because they told me so—through their expectations, patience, and nurturing. They taught me lessons about kindness, resilience, community, and the quiet power of believing in someone. And as I reflect on my own teaching, I realize I’m still learning from them, still carrying their influence with me in every classroom I enter. I thank them so much.