What I Learned From My Teachers

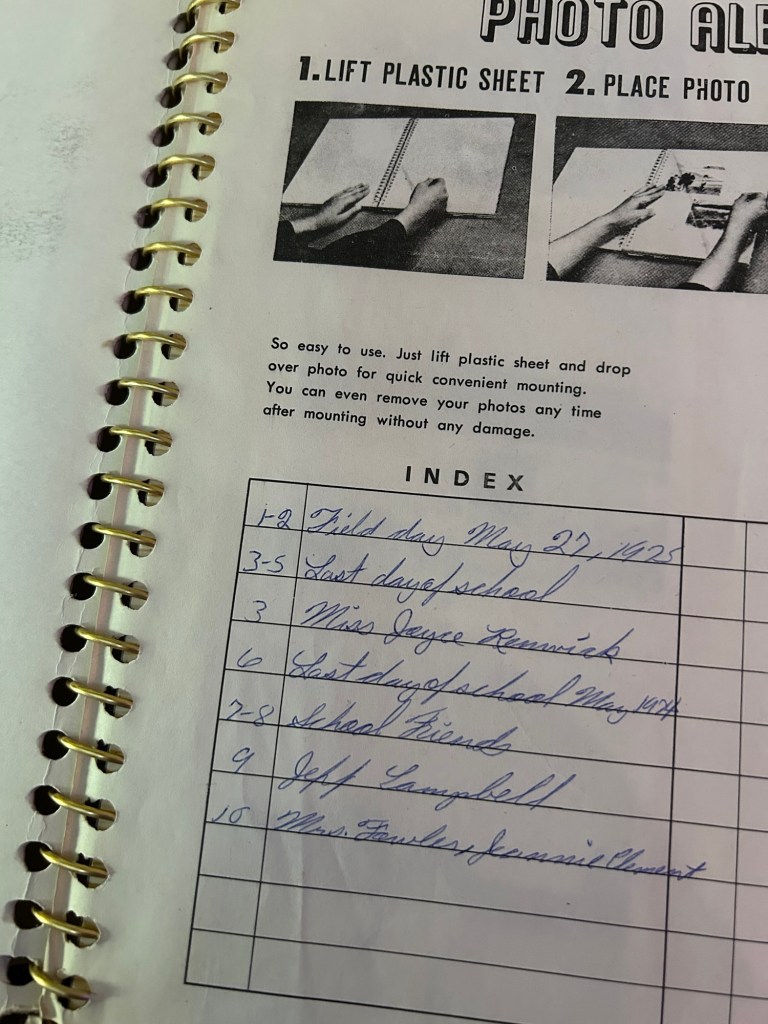

There’s a lot we carry from our school days—the lessons that stick, the ones that shape us in ways we only realize years later. I’ve been thinking about the teachers who left a deep impression on me, and how those early experiences continue to resonate as a quiet, steady presence in my life and work today. This piece (Parts 1 & 2) is dedicated to the teachers who shaped me, and I want to honor them by name.

Mrs. Hood, 1st Grade: Recognizing Potential

Mrs. Hood saw something in me from the very start. I still have the report card she wrote on: “Ugena is a good student, but she talks too much.” That one line captured a lot. It was the first sign that someone recognized my potential—and my tendency to let my mouth run ahead of me. I’ve held onto that report card all these years, a reminder of what it means to be recognized for one’s potential and ability. In first grade, we received our first “real” readers, Under the Apple Tree. I remember sleeping with mine under my pillow. Years later, I found a copy and treasure it as a symbol of my lifelong love of learning.

Mrs. Fowler, 2nd Grade: Be Kind and Carry a Red Paddle

Mrs. Fowler wasn’t just the first teacher to believe in me—she made me believe I was special. She had a way of balancing kindness with authority, and yes, she carried a red paddle as a reminder that rules mattered. But it wasn’t fear that motivated us in her classroom—it was the feeling that she cared. That balance of kindness and discipline taught me more than any lesson from a textbook. I also remember me, Jeannie Clement, and Susan Pace singing church hymns at the front of the class during school hours—something that feels almost unimaginable today, but back then, it was just part of the rhythm of life and learning in Mrs. Fowler’s class.

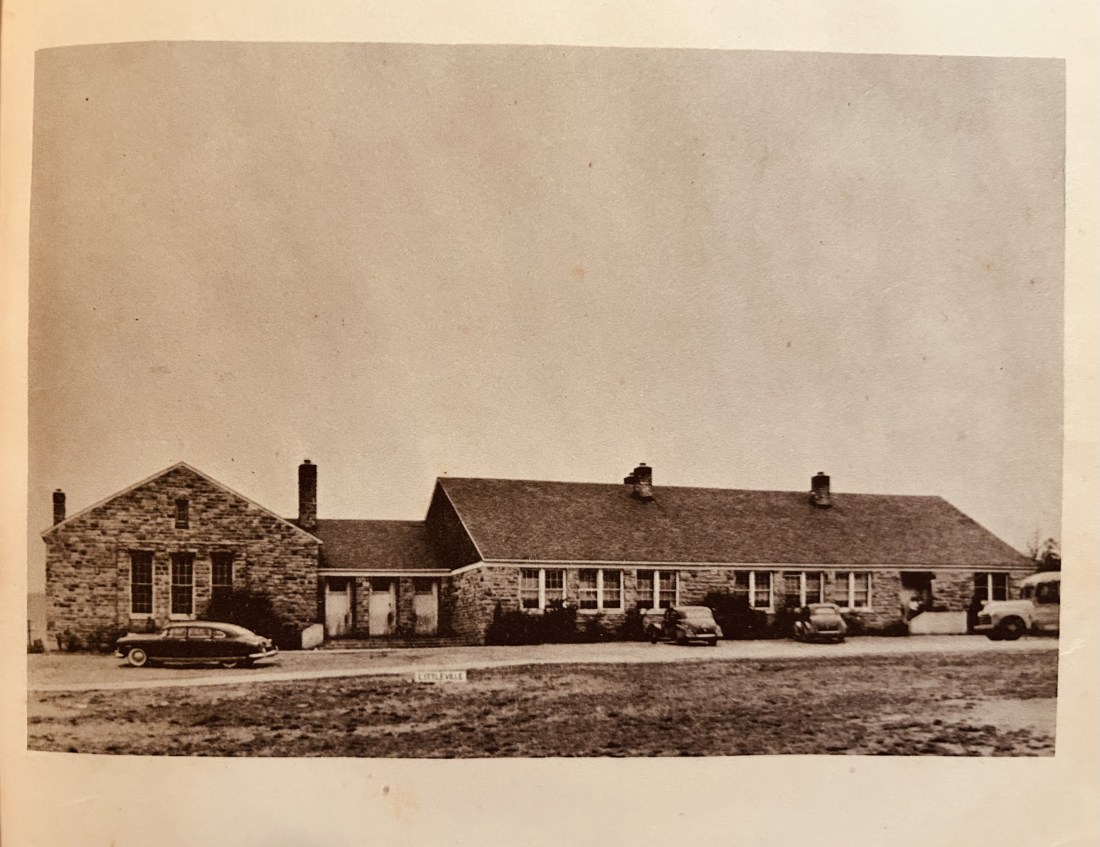

Mrs. Haley, 3rd Grade: You Can Do Hard Things in Challenging Places

Mrs. Haley was an African American teacher in an all-white school in Littleville, Alabama, in 1971. That alone was remarkable. But what sticks with me is how she tried to teach us about Dr. Martin Luther King—in a place and time where that wasn’t easy. She showed me that you can do hard things, even when the environment isn’t welcoming, and that courage can look like simply sharing the truth. I don’t know what happened to Mrs. Haley–what turns her life took. I hope she knows that in that little school room with green walls, she made a different.

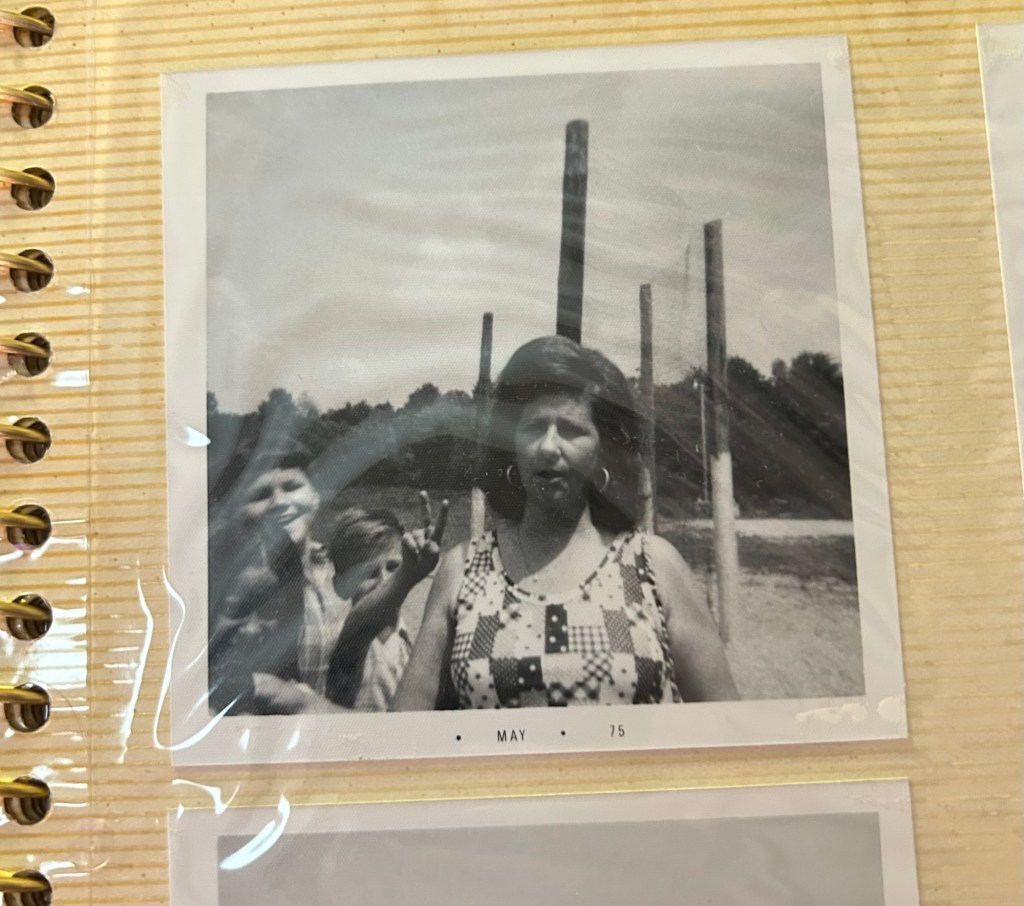

I was the narrator, second from left on right.

Mrs. Wimberly, 4th Grade: Finding Joy in Learning (and Neck Massages)

I absolutely adored Mrs. Wimberly. She had a way of making the classroom feel fun and alive. This was the year I first heard about the Osmond Brothers from Jeannie Clement, and while that might seem trivial, it’s part of what made school feel like a place where life happened. Mrs. Wimberly wasn’t naive either—she let us give her neck massages during PE, while having deep discussions about who was better, the Osmonds or Elvis. Looking back, I see that she knew how to keep us engaged, even if it meant a little creative classroom management.

Mrs. Wimberly was also the first person I had met who had seen Elvis live in concert. She gave me a photo book from the concert, and for Christmas, my mom got her the most wonderful present, which I had selected: a black plastic cat with diamond eyes and a fuzzy boa—filled with bubble bath. If nothing else, I have always been classy!

Mrs. Wells, 5th Grade: The Best Education, No Matter Where You Are

Following Mrs. Wimberly was no small task, but Mrs. Wells handled it with grace and grit. She was the only teacher I had at Littleville who actually lived in our community, and she took that responsibility seriously. When I complained that math was hard and had a fifth grade hissy fit, she didn’t let me off the hook—she made sure I learned fractions. Mrs. Wells held an Education Specialist degree, and my mother once asked her why she stayed at Littleville School when she could’ve worked anywhere. Her answer: “Our kids deserve a good education, just like anybody else.” That belief has stayed with me, a quiet reminder that showing up fully isn’t just about personal pride—it’s because others deserve the best we have to offer, no matter where we are. Mrs. Wells eventually became the principal of Littleville School and remained in that position until it was closed in 1994. (I have written about Littleville School in “A Memoir of Littleville School: Identity, Community, and Rural Education in a Curriculum Study of Rural Place” in William Reynolds’s collection, Vol. 494, Forgotten Places: Critical Studies in Rural Education (2017), pp. 169-188.). Mrs. Ann Wells lived to be 88 years old, and till the end of her life, when she saw my parents, she asked about me.

Miss Renwick, 6th & 7th Grade English: The First Crush

Of all my teachers, Miss Renwick is the one I’ve wondered about the most over all these years. I wish I knew what happened to her. Looking back, I know now that she was my first crush, as young girls often have. I adored her, admired her, and hung on every word she said. My poor mother spent countless hours waiting for me in the parking lot of Littleville School while I lingered in Miss Renwick’s classroom after school. I really appreciate that—both my mother’s patience and Miss Renwick’s willingness to let a student hang around after a long day. She introduced us to literature–not just stories found in “readers,” but the classics. She described the faraway places where they took place. “You can go to these places, see these things,” she told me. I’d like for her, wherever she is, to know that although I took a circuitous route, I did.

Mr. Sizemore, 7th Grade Science: The Surprise of Humanity

Mr. Sizemore was a science teacher with a presence that made us all a little nervous. He was the only teacher I ever had who effectively taught while sitting behind his chair, which he did almost every day unless he got up for the occasional lab activity. He wore the same clothes every day: a blue shirt, blue jacket, dark pants, and shined brogans. His black hair was neatly combed with Brylcreem—long after Brylcreem had gone out of style. He wore black horned-rimmed glasses like Clark Kent. He drove an old blue Ford truck, and his stern demeanor was enough to keep us on edge. We were especially scared when he’d slam his book on the desk if we weren’t paying attention. But I remember my daddy talking about running into him out in public, chatting about chickens like old friends. It surprised me to realize Mr. Sizemore had a first name—David—and a life beyond the classroom. Thinking about him today, I realize just how young he must have been in 1976. That small realization stuck with me: teachers are people, too.

To be continued in Part 2…